After almost seven years since we first mooted the idea, Helen Gebregiorgis and I finally took the first step in what may become a long series of exhibitions focused on the symbolism of beds. The roving exhibition was launched in January in Lagos and followed by a second in February in Abuja. We now hope to take this work to as many locations as are willing to host it.

Why beds? This is always the first question I get asked when presenting this idea. To respond, I situate the project within my own artistic practice. I think of my work as being concerned with the symbolism of everyday objects. I have previously created photography projects focused on life as a project, using the symbolism of incomplete buildings, doors and urban transportation in Africa. I value symbolism as a tool because it creates opportunities to engage with heavy subjects through familiar objects that people can easily relate to.

For example, incomplete buildings are common across many developing countries—projects that are started but never finished, yet continue to occupy space. These buildings reflect people’s real aspirations, achievements, failures and, in some cases, shame. An exhibition on this subject can therefore bring people together who might otherwise be unlikely to attend an event explicitly framed around abstract ideas such as life as a project.

Against this background, we chose beds because they are among the few objects that accompany us throughout life. Life itself is, in many ways, made in beds. Most people are conceived and born in beds. We spend much of our infancy in them, and as we grow, our relationship with beds evolves. It is often said that adults need six to eight hours of sleep each night; if observed, this means we spend roughly 25% of our lives voluntarily in beds. There are also periods of involuntary time spent in beds—during physical or mental illness, for example or severe restrictions caused by a public health event like COVID-19.

In adolescence, beds are often the first personal spaces we are given or claim as our own. When we can afford it, a bed is often one of the first possessions we buy for ourselves. As we age, we tend to spend increasing amounts of time in beds. Many people will die in a bed—whether at home in their sleep or in hospital, and, depending on religious or cultural practices, may also be laid in state or buried in one.

Across the life cycle, beds are experienced in multiple and often contradictory ways. They are places of rest, joy, intimacy, and connection—spaces where dignity can be restored and where we spend time with loved ones. Yet beds are also sites of violence, sickness, pain, and death. They can hold moments of healing and harm, safety and distress, love and loss. While beds may appear to be ordinary objects, they are often the settings for some of the most consequential events in a person’s life.

Beds, however, do not exist in isolation. They are embedded within social contexts and shaped by culture in their design, use, and meaning. They reflect societal values and expose wealth inequities. Beds are tied to spaces such as homes, hospitals, mental health institutions, temporary shelters, prisons, hostels, hotels, and homes for the aged. Without access to such spaces, many people lack the affordance of owning, or even sleeping in, a bed, no matter how basic.

Globally, homelessness forces many people to sleep rough, a situation often worsened by funding cuts and closures of institutions that support poorer and vulnerable populations. In many places, hospitals are unable to provide adequate care due to a lack of beds—a problem that becomes especially acute during public health crises such as Ebola and COVID-19. As cities develop and gentrify, urban transformation also contributes to the displacement of people who are left without a place to lay their heads. There is much to learn, unpack, relearn, and rebuild through this series of exhibitions, and I believe we have so far only scratched the surface.

Our exhibitions created space to reflect on many themes connected to beds, including love, grief, childbearing, gender roles, consent, memory, and dreams. Each exhibition was organised into five sections:

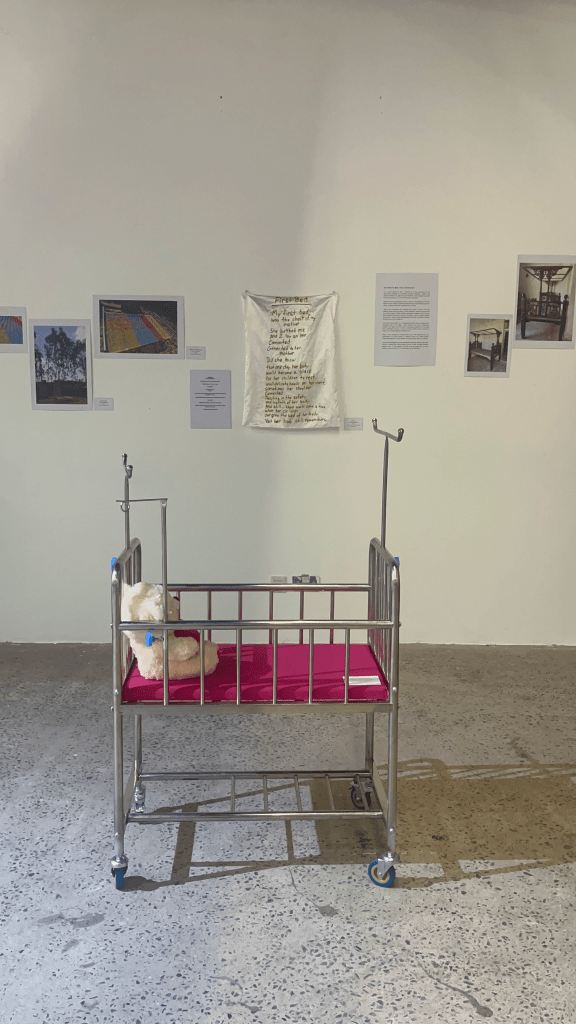

- Physical Beds: a communal bed, double bunk bed, infant hospital cot, and several mats.

- Rest and Meditation Area: a space set aside for relaxation, comprising mats, pillows, and cloth materials.

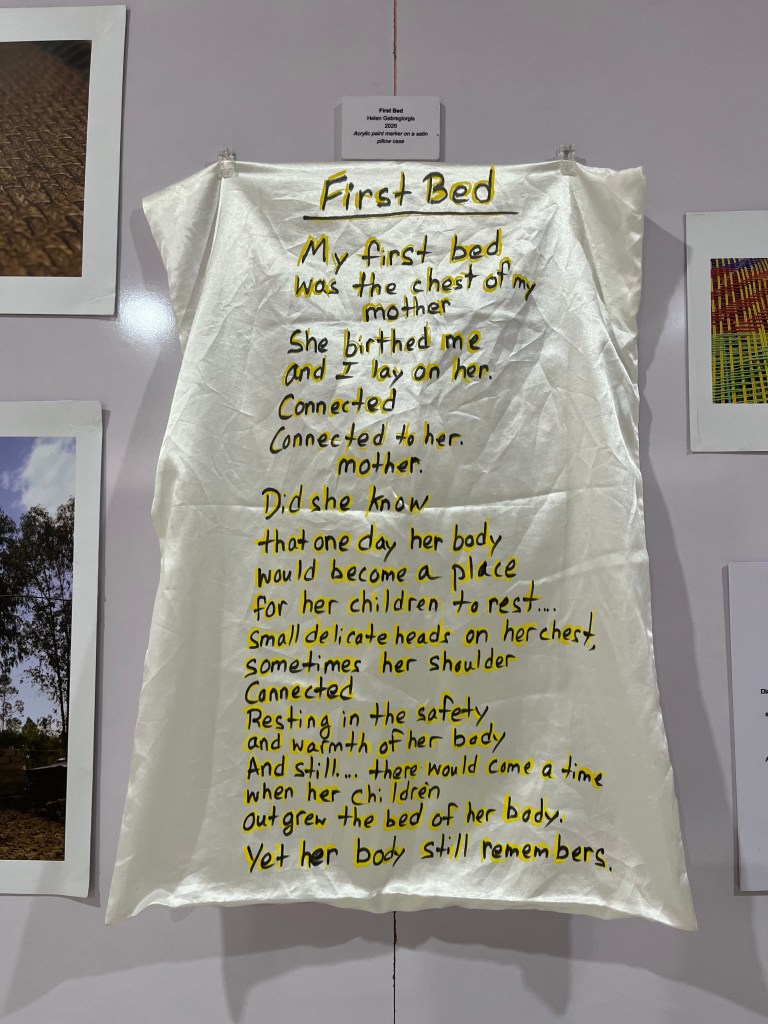

- Artists’ Reflections: our own photography, writings and poetry.

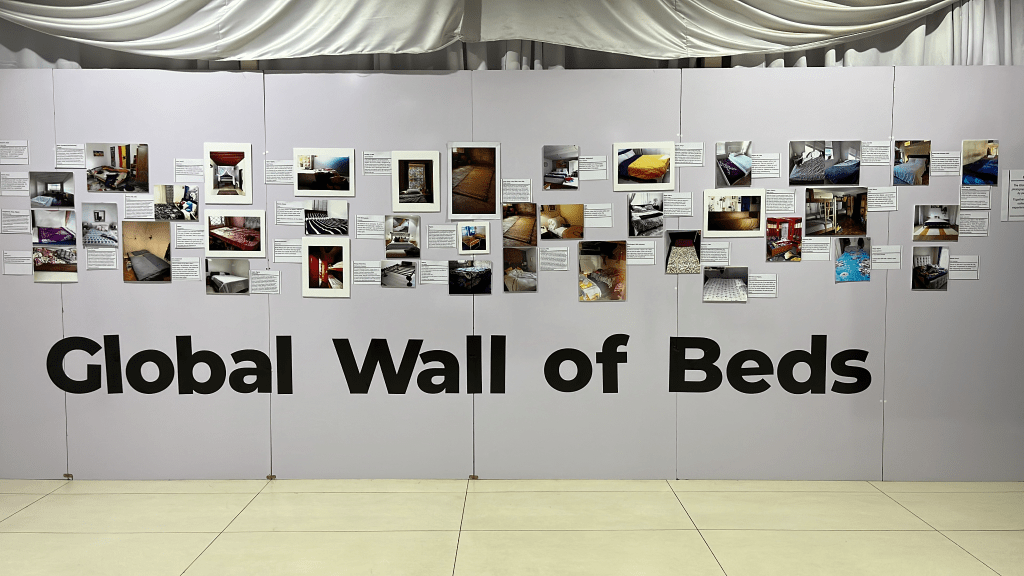

- Global Wall of Beds: a collection of bed stories and accompanying photographs submitted from around the world. To date, we have received contributions from 19 countries.

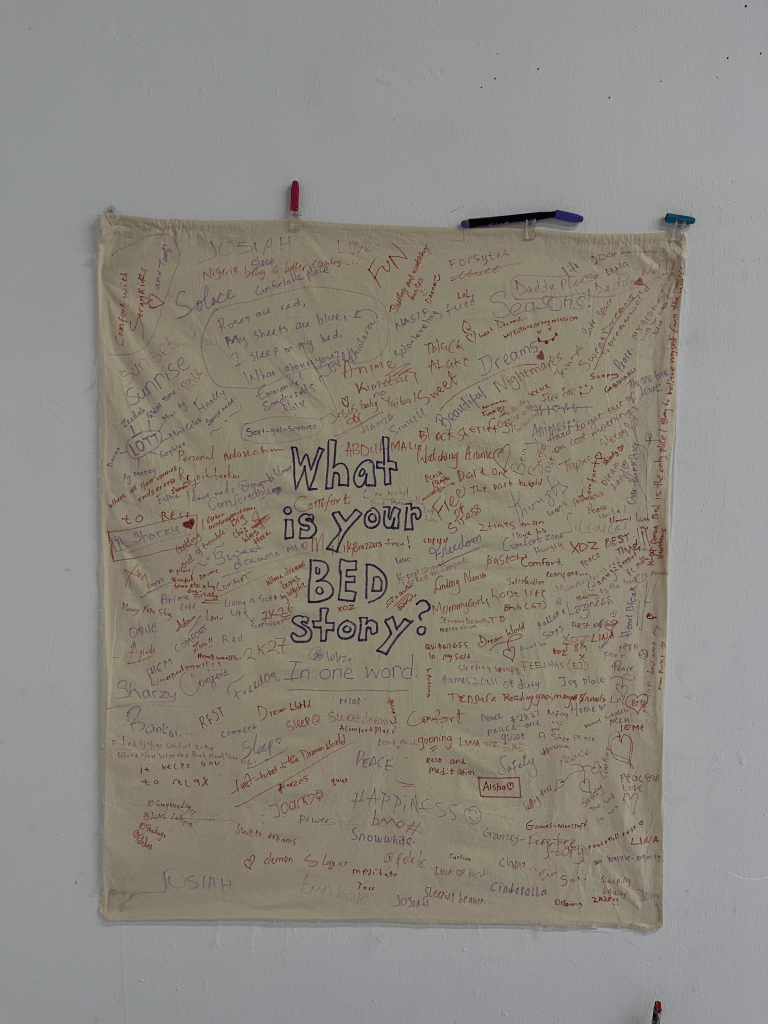

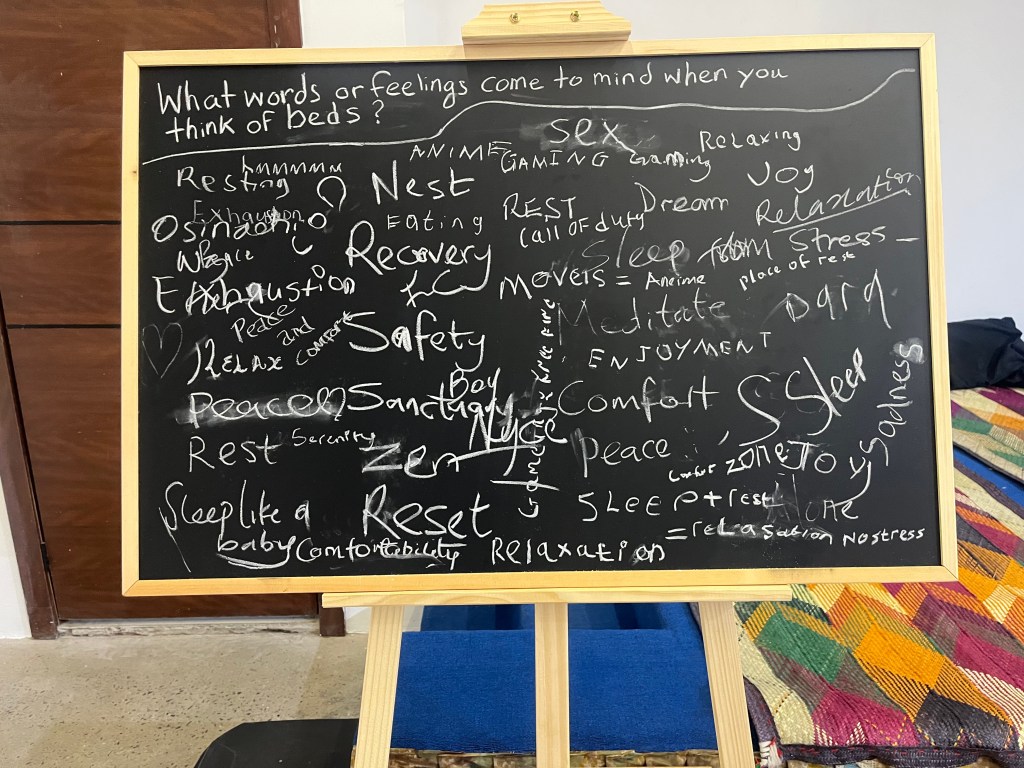

- Participatory Activities: including a recording booth for guests’ reflections, writing surfaces where visitors share words they associate with their beds, visual presentations of recordings, an audio loop and thematic workshops.

Our two exhibitions so far have been deeply revealing. We learned a great deal. In Lagos, many guests told Helen and I, and also through conversations, notes, and recordings, that they would never see a bed in the same way again. Similar reflections were shared by visitors in Abuja, including responses that approached beds from design and spatial perspectives, like this one, and a TV reporter’s detailed video description of the Lagos exhibition.

I am grateful to the Lagos Pop Up Museum and the Gender Mobile Initiative for hosting these exhibitions. I look forward to continuing this work and holding future sessions in other cities around the world.

This is incredible!!!

Symbolism is a great way to unravel subjects that are true to life.

Bravo!

Such a powerful reminder that everyday objects hold extraordinary stories.

Beds carry our memories; joy, healing, vulnerability, and also reflect the inequalities around us. It really is where life happens quietly; birth, illness, love, grief, rest, reflection. It just makes you realise that memory is not only carried in people, but in the spaces that hold us.

A simple object, but a profound symbol of what it means to be human.

Yes bed reminds us of our daily relationship with life. Outside the physical symbolism what are the spiritual relationship witj bed